I have played a lot of games this summer. Here is a list of them along with brief commentary.

First, as an overview, the list:

- Dark Souls 2 (140 hours, finished)

- Thief Reboot (finished)

- Anna: Extended Edition (finished)

- Knock-Knock (finished)

- Castlevania: Circle of the Moon (finished)

- Mountain (finished)

- Catachresis (finished)

- Metal Gear Solid (2/3′s complete)

- Metal Gear Solid 2 (almost finished)

- Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance (3/4′s complete)

- Darksiders 2 (3/4′s complete)

- A Dark Room

- Frog Fractions

- Fallen London

- Ghost Rider (played the first two levels)

- Assassin’s Creed III (played the Kenway section and started Connor)

- Hitman 2: Silent Assassin (played two missions or so)

- Tenchu: Stealth Assassins (played a little bit)

- Castlevania: Order of Ecclesia (played a few levels)

- Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin (played a few areas)

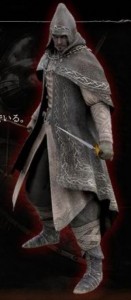

Dark Souls 2 (140 hours, finished): The Souls games are my favorite franchise, and I enjoyed Dark Souls 2 deeply, fervently . . . enough to play it for 140 hours, which translates into full-time play for a few weeks. I think it’s a lesser accomplishment than the previous games, but that’s like saying that pure gold is less valuable than pure platinum. DS2 takes a maximalist approach, with more of everything than previous games spread out over a larger world. But the metaphysical subtlety, narrative richness, and spatial density that were the hallmarks of the previous games have diminished along with the loss of Hidetaka Miyazaki as lead designer. I liked Demon’s Souls better. That said, I was deeply absorbed in Dark Souls 2, and its gorgeous Gothic art style, haunting music, and absorbing gameplay are still second to none. In particular, I enjoyed the opportunity to be a Hexer: a warlock class that draws its power from the lower of the faith and intelligence stats, requiring the player to level up both values evenly. This class had the perfect associated convenant: the Pilgrims of the Dark, a PvE covenant that privileges exploration of obscure nooks and crannies in hidden areas. This sense of the hidden, far more than any clearly defined evil, is the meaning of the Dark in this world, and the simultaneous mechanical reliance on faith and intelligence thematically reflects the driving personality traits of an obsessed loremaster: the faith to be drawn to the metaphysical world of gods and covenants that may not exist, and the intelligence to explore them analytically.

Thief (reboot) (Finished): I enjoyed Thief despite its mediocre reviews. The game doesn’t hold a candle to the original series, though. The games side-quests, called “jobs,” are the best part, since they reveal the densely honeycombed secrets of the City hub (which is otherwise frustratingly designed when its dead ends impede progress through the main mission).

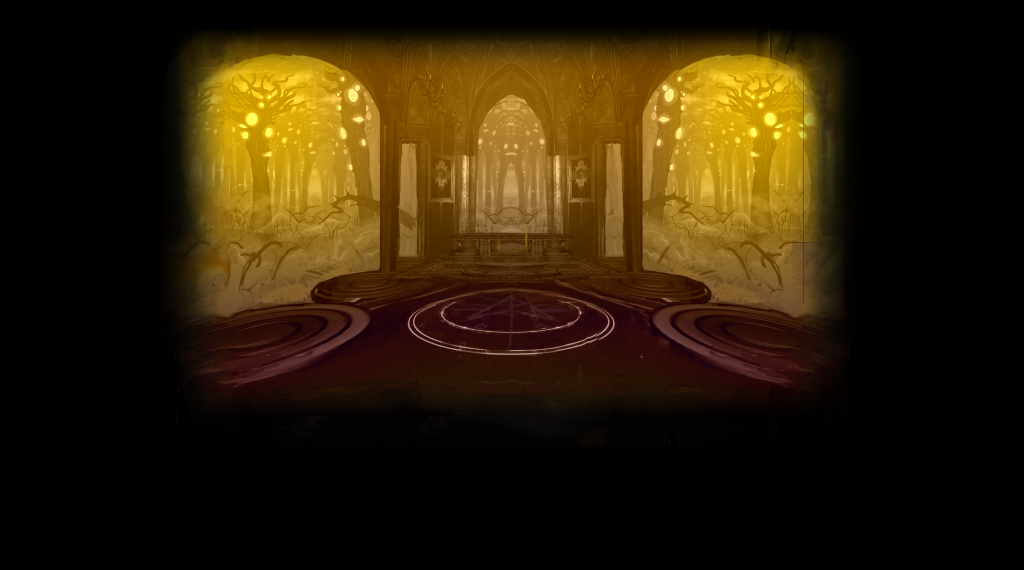

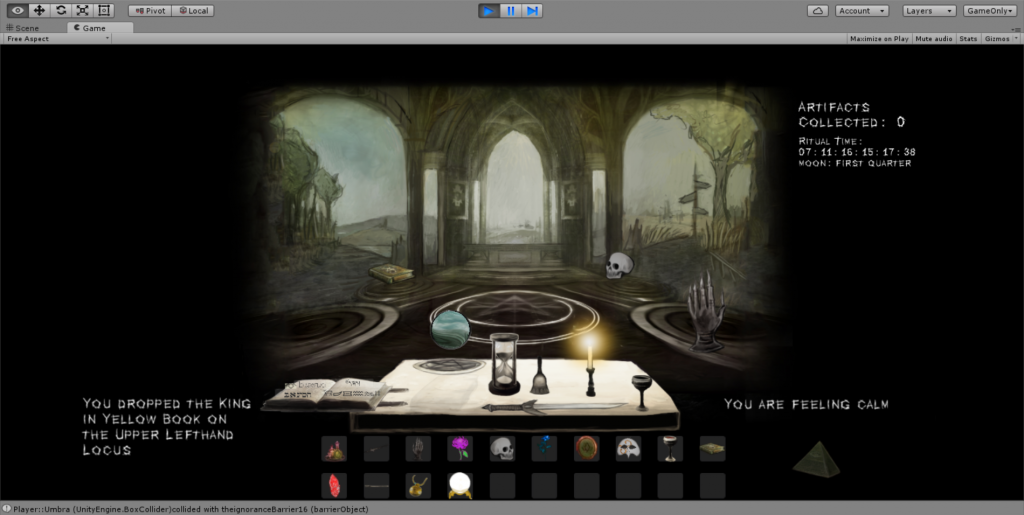

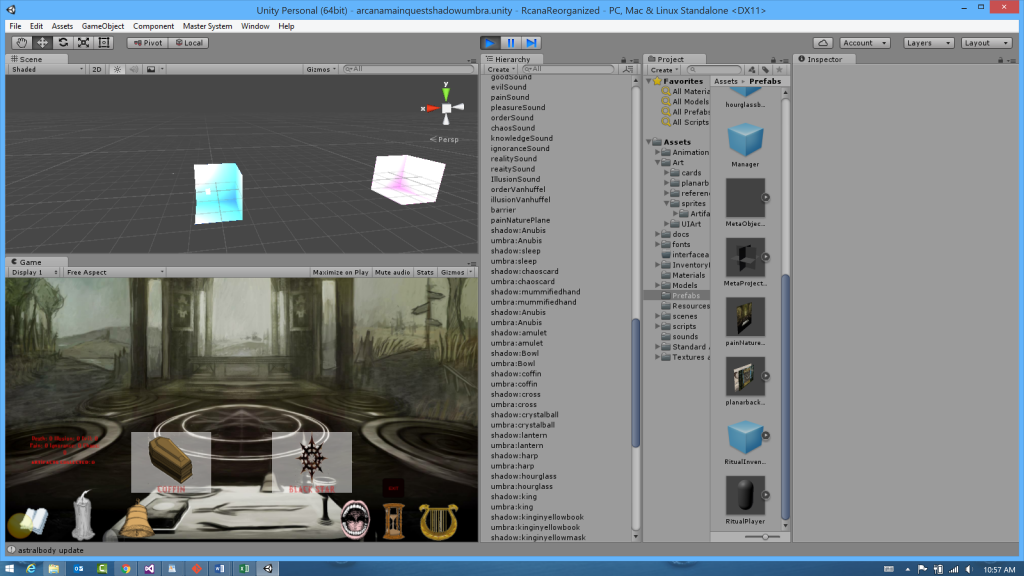

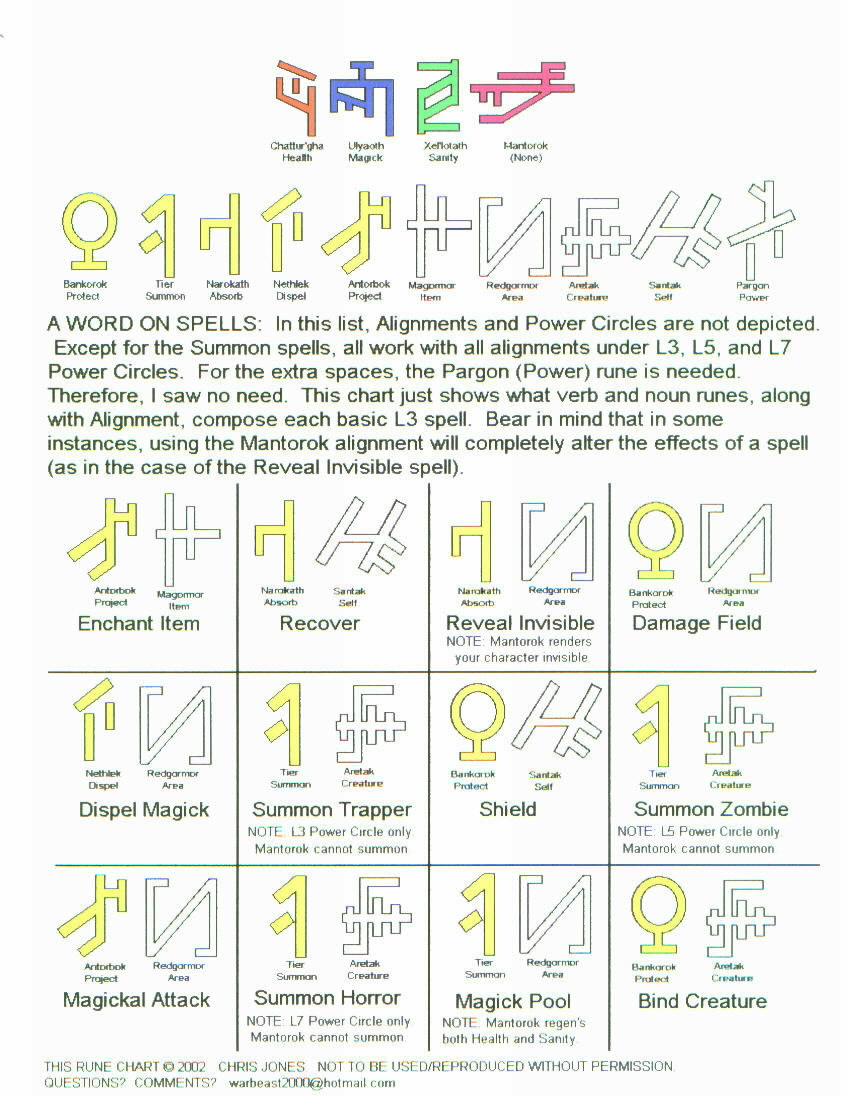

Anna: Extended Edition (finished): A striking implementation of ritual magic in a first-person horror adventure game. Probably the best thing I played this summer (tied with Fallen London), with clear design similarities with Arcana: A Ceremonial Magick Simulator, and much potential inspiration for the Arcana Ritual Toolset.

Knock Knock (finished with a bad ending): A haunting mystery game. Along with Anna and Year Walk, Knock Knock rounds out what I think of as the holy trinity of inscrutable supernatural mystery games. The horror genre has, for me, always been poorly named, since being scared isn’t the main appeal of these games for me (or at least the subset of horror games that I enjoy). Games like Knock Knock allow players to explore the metaphysical mysteries of existence in the full knowledge that they will remain mysteries. In the case of Knock Knock, the game’s most basic mechanics are cryptic, giving the game a deeply spooky atmosphere.

Assassin’s Creed: Revelations (finished): For me, the AC franchise is all about setting, and the gold filigree of the Byzantine empire is as rich a world as one could ask for. The intertwined fates of Altair (my favorite assassin) and Ezio (who is vastly more interesting with the maturity of old age) are communicated through embedded playable flashback sequences that are pleasantly . . . Byzantine. There is still enough emphasis on stealth here to preserve the fantasy of secret assassins, with not a pirate ship in sight.

Castlevania: Circle of the Moon (finished): Part of my lifelong quest to play all Castlevania games on all platforms, and a justification for my purchase of an ancient Game Boy Advance. Unique features and traits here include a well-designed card-based magic system that encourages exploration, a high difficulty curve relative to the other handheld Castlevania games, and an overall dark color palette. Like many Castlevania games, Circle of the Moon also lets the player wield a flaming chain-whip . . . a feature that I’ll return to later in these reviews. After experiencing deep spontaneous joy while fighting a naked succubus who was riding a giant skull, I started tagging these sorts of gaming experiences as #justmetalthings, realizing that the thrill here was analogous to living inside a heavy metal album cover.

Castlevania: Harmony of the Dissonance (70% finished): In stark contrast to Circle of the Moon, this game is fairly easy and has a bright color palette. Its one distinguishing feature are two castles that overlap on different planes or layers of existence, so that clearing an obstacle in one castle can open a path in another. This layered effect is an interesting variation on the inverted castle of Symphony of the Night and requires a bit more subtle thought about the spatial relationships between both castles (which are spatially harmonious and dissonant, in the words of the game’s title). The architectural superimposition of the castles has narrative metaphysical implications, since one of the characters acquires two souls via vampiric possession and mentally creates the castle out of his spiritual conflict.

Catachresis (finished): [spoiler alert] Intriguing adventure game that implements the concept of powerlessness in the face of cosmic horror by providing a story in which the player can do nothing to alter a linear storyline. Rich, evocative writing that exploits negative space effectively but then drops off abruptly.

Murdered: Soul Suspect (played about 2/3′s of the game): This detective adventure game, which I played on the PS4, has some engaging investigation mechanics that encourage actual thought about how the clues of the case relate to each other. (In this respect, investigation of crime scenes is superior even to the excellent Deadly Premonition). There are some irritatingly clunky quasi-stealth mechanics involving demon evasion that break the flow of the otherwise excellent narrative.

Metal Gear Solid (played about 3/4′s): This classic stealth game in many ways defines the genre, on which I’ll be teaching a class in Fall 2014. The sneaking aspects of the game are tough but engaging. The bosses, while sometimes deeply creative, are often frustrating to me.

Metal Gear Solid 2 (almost finished): The above comments on MGS1 still apply. [spoiler alert] The sequences toward the end in which the game deconstructs itself are jaw-droppingly, mind-blowingly brilliant in that they are both shocking and thematically dense, eschewing the cuteness that mars so much breakage of the fourth wall in games and other media.

Darksiders 2 (2/3′s finished): The best Skeletor simulator ever made. One of the many games I’ve played this summer with an aesthetic heavily influenced by the style and iconography of metal music. #justmetalthings

A Dark Room: A text and ASCII-based adventure in the style of Candy Box, but with less quirk and whim. The gradual unfolding of a mystery over time draws me into these games, but only some of them continue to hold my interest.

Frog Fractions: A parodic edutainment game with many quirky and gradually emergent features. The lead designer states that his intent was to make a game that felt as mysterious as every game did in the 1980′s (when, presumably, scarcity of documentation and few conventions of gameplay made it feel like anything was possible). This design intent fits well with “Howard’s Law of Occult Design,” which I spoke about at GDC Online in 2012 and then wrote up for the book 100 Game Design Principles. “Secret Significance is directly proportional to Seeming Innocence × Completeness”: the power of secret significance is directly proportional to the apparent innocence and completeness of the surface game.

Fallen London: (China) Mieville meets Farmville. This browser-based story game competes with Anna as the best thing I’ve played this summer. It delivers on the sense of gradually unfolding mystery over time to which A Dark Room aspires. Its setting is an infernal London that has fallen both in the literal spatial sense (collapsing due to the weight and/or evil influence of the Grand Bazaar) and in the spiritual sense, selling its soul to invading devils. The writing is superb, evoking the aesthetics of Mieville without his doom-laden and heavy-handed politics. The opportunities for story-based role-playing are superb, and small fragments of poetic prose are about the only reward that could not only compensate for Farmville-style appointment mechanics, but actually render them magnificent. Fallen London has recently expanded into a graphical sea-faring roguelike called Sunless Sea, which is set in the same universe as Fallen London. A tabletop roleplaying game also appears to be in the works. Like all great transmedia, this world-building succeeds because I want to spend as much time in this universe as possible, and through as many different gateways.

Ghost Rider: One of my revelations this summer is that I will play and enjoy anything in which Iets me hit things with a flaming chain whip. Ghost Rider offers this opportunity in spades. In many ways, it is a God of War clone, but these are far from damning words to me. The cloning is well-executed and appropriate in this case: true to the infernal violence of the source material. Equally true to the stunt riding background of Johnny Blaze, Ghost Rider includes exciting motorcycle sequences that allow the player to soar over roller-coaster size stunt jumps, including a stunt-riding sequence in hell. I am afraid to watch the Ghost Rider movie on which this was based out of fear that it will, despite popular derision, turn out to be my favorite superhero movie. When Nicolas Cage prepared for the role using his self-proclaimed “nouveau shamanic” approach, painting his face in Baron Samedi skull makeup and sewing tourmaline amulets into hidden pockets in his leather jacket, I think he was onto something, some primal demonic energy at the heart of this uber-cheesy franchise. Spawn (and its equally terrible and wonderful videogame spinoffs) taps into the same fire.

Mountain: an experimental art game that, like many experimental art games, stretches the boundaries of the word “game.” Another slowly-unfolding experience that comments metaphorically on the lonely, often absurd, sometimes beautiful progress of a lifespan. I find that these experiences work best when accepted as they are. I did.

Assassin’s Creed III (played the Kenway sequence and a little bit of Connor): Because Assassin’s Creed is all about exploring an exotic, ancient setting for me, I disliked playing in America. The engine feels polished, glossy, and vacant of most of what made the previous installments absorbing.

Tenchu: Stealth Assassins: I played a little of this PS1 game because it is one of the first examples of the stealth genre. The controls and interface were difficult compared to a more recent and polished installment of the franchise (Shinobido 2: Way of the Ninja).

Hitman 2: Silent Assassins: I played a couple stages of this game in preparation for my upcoming stealth class. I liked the controls and the atmosphere, as well as Jesper Kyd’s orchestral score and the use of disguise as a game mechanic.

Castlevania: Order of Ecclesia: I played several levels of this game, which has fantastic art direction and an engaging combat and magic system involving glyphs (enemy powers that can be equipped as weapons, mapped to the X and Y buttons, and duel-wielded to create strings of attack combos).

Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin: I played a few minutes of this game. The premise of paintings as otherworldly portals in Dracula’s Castle is intriguing, and I will inevitably return to the game as part of my Castlevania quest. The unique mechanic is the ability to switch between two characters who constantly follow each other as a tag-team. While this mechanic results in some interesting puzzles, it also detracts from the experience of being a lone hero against overwhelming darkness, which is at the heart of the series’ Gothic thematics for me.