Demon’s Souls is a dark, mysterious opera whose theme, expressed through gameplay and the unfolding of a powerful narrative, is the lure and peril of Faustian bargains. By opera I refer not just to the game’s occasional bursts of swelling sound, or even to solely to its understated yet epic narrative. Rather, I use the term in the same way that Richard Wagner envisioned an ideal future form of opera as “gesamkundstwerk” or “total artwork,” in which every aspect of music, libretto, costuming, and set design fused together to create an interactive, participatory mythology.

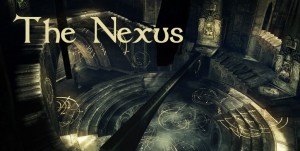

Demon’s Souls strikes me as operatic both in its overarching structure and its minute details; I first noticed this aspect of the game when looking at the loading screens between the game’s areas. These screens are a joy to pore over, as they provide larger-than-life full portraits of the game’s various characters, each dressed in some variation of black and gold. The characters’ costumes, lovingly rendered with the lush visual textures made possible by the PS3’s high-end graphics capabilities, look more like opera costumes than the typical orcs-and-elves garb. And, as in the best opera, these details contribute to a larger aesthetic and thematic end that manifests partially in the game’s black and gold color scheme. From the first moment in the Nexus, the game’s central quest hub, the shining obsidian walls glow with overlapping layers of golden sigils right out of some arcane grimoire. As we discover through the game’s hard-won fragments of narrative reward, gold is the color of demonic magic or “soul arts” in the fallen kingdom of Boletaria. This visual symbolism lends a dark edge to one character’s reminder to the player: “you have a heart of gold . . . don’t let them take it from you.”

Many aspects of the game resonate to the tune of an overriding aesthetic principle, expressed in disparate parts working together. This principle takes the form of a question, which might be formulated with the Biblical question “what profiteth it a man if he gains the world and loses his soul?” In the case of this game, the “soul” of the verse might be better modified to “souls,” since the demon’s souls of the title are the currency of exchange in Boletaria and the only way of increasing stats, leveling up, buying items, and acquiring spells. Demon’s Souls is an arduously, unrelentingly difficult dungeon crawl in which success is possible only through the tireless trial-and-error of multiple deaths and the careful cultivation of community knowledge and cooperation. Other reviews, such as those of Michael Abbott (a.ka. the Brain Gamer) and Gamasutra, have offered excellent analyses of the game’s innovative online features and their close relationship to game’s educational element. I’ve also briefly written about some of these features in comparison and contrast to other online games in an interview with Randolph Carter at grindingtovalhalla.com.

In this entry, I’m less concerned with these features and more with a resulting experience of gameplay: the experience of temptation. While Demon’s Souls is unquestionably a game that challenges, it is also a game that tempts. Because each new corridor and secret passage bristles with difficult-to-reach exotic treasures and haunting encounters, the game constantly teases the player with the dilemma of continuing onward to fresh challenges, or retreating while one still can with one’s stock of souls. One misstep sends an unwary player back to the very beginning of a level and strips her of all unspent souls, creating a very powerful and excruciating form of negative reinforcement. One often knows, naggingly, in the back of one’s brain, that discretion is the better part of valor, that one should stop while one is ahead and cut one’s losses by returning to the Nexus after accumulating any sizable chunk of souls. Yet, the game quietly whispers in one’s ear: “come on, go just a little further, there are untold wonders around that corner.” More often than not, listening to that voice, to the suave devil on one’s shoulder, leads to the disaster of losing one’s souls.

And that is the classic Faustian bargain: recklessly seeking power and knowledge at the price of the most precious spiritual essence. The game quietly but insistently reminds players that such bargains are by their very nature losing games in which even apparent success can be as damning as failure. When one does efficiently spend souls, one can gain tangible power—power in some cases so great, as in the high-level spells earned through defeating a Greater Demon, that it intoxicates. Yet, the wisdom of this method of gaining power through the harvesting of souls (sometimes of demons and sometimes of their wretched, addled victims), seems dubious at best. Soul exchange is especially risky given the backstory element that Boletaria was corrupted, and the archdemonic Old One awakened, through the use of Soul Arts. There doesn’t seem to be much escape from Soul Arts for, while a pious priest condemns the use of magic as demonic, and his magician counterpart preaches the glories of humanistic progress over binding superstitions, both magical and priestly arts involve trading in souls. As Matthew Weise has pointed out, there are subtle but strong metaphysical implications in the game systems, through dialogue and other clues, that magic and orthodox religion are both highly similar in their methods and moral (or immoral) valuation. They are also both equally useful from a gameplay standpoint: priestly miracles serve the standard healing and protective functions, while magic provides a variety of offensive and defensive effects.

(On a sidenote, the priest’s self-righteous, monotheistic glorification of the “God of this world” at the expense of other spiritual traditions evokes a mistrust in me that no doubt comes from many places, including a background in some Gnostic traditions, in which the apparent god of the visible world turns out to be synonymous with the demonic Archon. I’m anticipating a Lovecraftian switcheroo in which the priest turns out to be worshipping the Old One. I also notice slight implications that religion and solipsism may be mildly intertwined with each other, since the most costly Banish “miracle” allows players to negate the PvP aspect of the game, driving off the Black Phantoms of other players.)

However, I’m also fairly sure that, despite my class decision to be primarily a magician who totes a miracle talisman in his left hand as a healing insurance policy, the more esoteric and humanistic ambitions of Sage Freke the Visionary are just as dangerous and reckless; the exchange of souls for magical power is, after all, the classic Faustian bargain. Even if a fighter-class player managed to avoid the lure of both talisman and wand, religion and magic, he would still have to level up. And every attempt to level is accompanied by a haunting question from the Maiden in Black, the game’s central quest-giver: “Dost thou seek Soul Power? Then touch the Demon inside me.” Based on observations of other characters, major and minor, who have had congress with demons, the results don’t seem pretty. The presence of a character named Mephistopheles in a loading screen (I haven’t encountered him yet) suggests that these Faustian parallels are quite intentional and self-aware on the part of the developers at From Software. How deep or sophisticated these intentions ultimately go is less important to me than the way that insinuations and implications emerge from the synergistic fusion of the game’s mechanics, aesthetics, and narrative, from the single-player and social interactions that develop from the game’s intricate and beautifully, if somewhat sadistically, balanced systems.

I haven’t finished Demon’s Souls (I’m 59 hours in, not counting 10 hours spent on an abortive character), but I’m going to go ahead and make a statement that I’ve been mulling over for a while now, reluctant to seem rash or fanboyish. Demon’s Souls may be the best game I have ever played. (There is still a bit of a running competition with my other favorite game, Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem, which remains an example of top-notch design that may even bear some aesthetic and gameplay resemblance to Demon’s Souls.) Each (comparatively rare) time I progress in Demon’s Souls, new mysteries open up, and these narrative discoveries are buoyed up by the inherent pleasures of persistent challenge, intermittent reward, and aesthetic gorgeousness.

(Possible spoiler alert): Last week, at the gloriously and disturbingly nightmarish second portion of the Tower of Latria, I suspected that Demon’s Souls may have finally reached the threshold of my expectations for inspired level design. Last night, during an unexpected sequence that resulted from a mysterious narrative backfiring of the now-routine attempt to summon a co-op player or Blue Phantom, I became pretty sure that this is a game like no other. I can’t describe the sequence without entering full spoilerdom, but I will say it involved a room full of chairs and a large orange turban.

It is a testament to the design of this game that it can both inspire enthusiastic accolades and a cautious reluctance—the feeling of falling into a trap, a metaphysical and moral conundrum that insidiously creeps up on unwitting players and then pounces, to a soundtrack of blaring brass and sweeping strings. Like the voice of a demon. Like the sound of an opera.