For a while now, I’ve been thinking about a concept in game design called the daimonic sublime: an experience of elation in response to infernal grandeur, derived equal parts from the fusion of Miltonic demonic defiance (“better to reign in hell than serve in heaven”) and heavy metal rebellion (heard in this 8-bit version of Opeth’s Grand Conjuration). The daimonic sublime increasingly draws together many threads of design for me, so where to begin in this network is necessarily somewhat arbitrary. I’ll start with two games at the top of my playlist and proceed backward to their roots in an ancient and unique CRPG, then move forward again in time to more recent concerns.

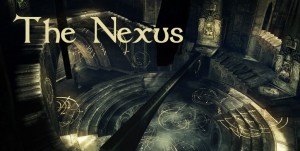

A particular thread in the tapestry of this concept relates to the games Demon’s Crest and Hungry Ghosts produced by Tokuro Fuwara. Fuwara is most famous for his work on Ghosts and Goblins, a series of side-scrolling platformers featuring an armored knight battling supernatural creatures through levels notorious for their brutally unforgiving difficulty. Demon’s Crest is a reboot of a sidestory or gaiden of the Ghosts and Goblins series featuring a red demon named Firebrand. Demon’s Crest is famous for its dark, melancholy atmosphere and intense difficulty, as signified by plunging the player in media res into a difficult and unskippable boss fight in the first moments of the game. Hardcoregaming101 features an excellent review of Demon’s Crest that concludes by describing Demon’s Crest as “a combination of all the best elements from Mega Man X, Super Metroid, and Castlevania.” In addition to Demon’s Crest, Fuwara also produced a Japan-only horror adventure game for the PS2 called Hungry Ghosts (a.k.a. The Lair of the Hungry Ghosts), which exhibits several features key to my own ambitions as a player and designer. Specifically, Hungry Ghosts uses first person perspective for gameplay mechanics other than shooting—namely, interaction with a surreal and treacherous underworld using a hand that can be extended and retracted using the right analog stick. This immersive perspective and control scheme used to heighten involvement in a dark world evokes the earlier Thief: The Dark Project (a first-person sneaker) as well as the later Amnesia and Penumbra series made by Frictional Games. Yet, what little I’ve played of Hungry Ghosts suggests that it is much stranger than any of these games because, in part, of the alternate cultural background of Tibetan Buddhism and its peculiar vision of an ambiguous limbo between afterlife and reincarnation. Demon’s Crest and Hungry Ghosts are near the top of my own personal backlog, perhaps below the extended King’s Field series that I’m currently working through. Hungry Ghosts is an obscure Japanese PS2 game that taps into a deeper vein of the daimonic sublime, a nexus where mechanical difficulty meets evocative narrative and aesthetic darkness to produce an experience that is greater than the sum of its parts.

While I’m talking about the daimonic sublime and first-person perspective, I would like to mention a much older game at the heart of my own design philosophy: Wizardry IV: The Return of Werdna. The first two Wizardry games pioneered the Western CRPG, with its wireframe dungeons and first-person exploration. The Wizardry series is roughly contemporaneous with The Bard’s Tale series and Ultima, all of which are in some sense direct computer ports of the core mechanics of tabletop RPG’s like Dungeons and Dragons. Early Wizardry is in some ways starker and more minimalistic than Ultima or The Bard’s Tale because of the absence of a top-down overworld and the strict adherence to wireframe dungeon graphics in black and white.

Wizardry IV intensifies these darker tendencies dormant in Wizardry and turns the mechanics of a dungeon crawler on its head in order to produce what several players, including CRPG historian Matt Barton, have called the most difficult CRPG of all time. Specifically, the game reverses the scenario of the first game, in which a single player controls a party of adventurers who descend through a ten-level dungeon to recover an amulet from the evil wizard Werdna. In The Return of Werdna, a single player takes the role of Werdna himself, who must ascend through the same ten-level dungeon in order to recover the amulet stolen by the part in the first game. Stripped of his powers, Werdna fights his way through a dungeon prison that has morphed into something exponentially more difficult than what he first faced. Whereas the dungeon of Proving Grounds was a standard orthogonal maze that could be fairly easily mapped on graph paper, Werdna’s prison culminated in a vast and ever-changing three-dimensional Rubik’s cube of corridors, chutes, staircases, and teleporters. (The director of the excellent film Cube was either deliberately inspired by this concept or unintentionally evoking it; either way, the Werdna concept has the same existential resonances of the film, in which a perpetually changing maze serves as a metaphor for pure disorientation and a desperate struggle to survive by only one’s wits). Werdna also featured save points in the form of pentagrams which re-set all the enemies on every level and served as the game’s only opportunities to gain back Werdna’s library of spells. The game actually featured a keystroke logger that invisibly recorded player’s every typed character and then penalized them for wasted strokes by only granting the Grandmaster ending to those who finished below a number of keystrokes. Werdna rewards caution and cunning, eking out every possible advantage from a system of RPG mechanics that have been exploited to produce complex and subtle puzzles. Unlike many CRPG series, Werdna does not simply extend or expand the world and mechanics of the previous games in a way that would be accessible to a newcomer. Rather, the game assumes and demands knowledge of the series’ gameplay systems (“for expert players only,” said the box cover) because it uses these systems to twist and subvert the conventions of the dungeon crawler, turning an RPG into a twisted puzzle adventure game.

And this shift in difficulty accompanies and resonates with an accompanying inversion of the storyline to become darker and more evil. Evil is as evil does, and a diabolical narrative and art style should naturally be accompanied by equally insidious difficulty in mechanics. This is one lesson at the heart of Demon’s Souls and its upcoming sequel, Dark Souls. The difficulty level of the game is inseparable from the grim darkness of its world as reflected in its narrative, art style, and audio. Moreover, part of the difficulty of the game stems from determining exactly what is evil. When players are deliberately prompted to identify with the evil nemesis they themselves defeated in the first game, the world has become topsy-turvy and ambiguous. Who ultimately is more cruel: an evil wizard quietly lurking in the bottom of a dungeon, or the opportunistic adventurers who blithely stole his amulet and left him imprisoned in a torturous prison? Which is worse, a demon king Allant, the demon-possessed Maiden in Black who spurs countless souls to struggle against him (for reasons never entirely explained), or the players who harvest the souls of monsters and other player to fuel their own doomed quests? “Evil be thou my good,” says Milton’s Satan, just as Clive Barker’s puzzle-wielding cenobites dub themselves “demons to some, angels to others.” To succeed in the world of the daimonic sublime, we must either become demons or develop a sympathy for the devil. It’s a hard lesson to forget.

When I first read an interview with lead designer Andrew Greenberg (whose reversed name is encoded in Werdna), Wizardry IV became my second archetypal game, the Platonic Idea that has governed virtually everything I’ve read, played, or designed for many years. (The first archetypal game was Brian Fargo’s adventure game, The Demon’s Forge, which has recently been rebooted as the modern dungeon crawler Hunted: The Demon’s Forge. Hints of the daimonic sublime were already in the original Demon’s Forge, in which a player must escape from a surreal dungeon ruled by a demon by solving a serious of difficult and twisted puzzles. The game must have sparked much of my early feeling that the universe was a prison that could only be escaped by solving its puzzles and mysteries).

Cue the King’s Field franchise, a series of notoriously difficult first-person RPG’s for the Playstation, of which Demon’s Souls is the avowed spiritual successor. King’s Field privileges exploration and caution over blind monster-slaying. Reading through the reviews of the series from its fans, the devotees of King’s Field consistently stress that the draw of these games is their darkness and genuine mystery, the way that players slowly solve puzzles to move forward through cryptic labyrinths, meticulously mastering relatively small levels in order to make incremental but exquisitely satisfying progress. The King’s Field series sows all the seeds of Demon’s Souls, and I’ll observe that King’s Field II (King’s Field III in Japan) may do the most to sow these seeds more successfully. I would argue (and will argue in a later blog) that the King’s Field and Shadow Tower series are crucial and iterative approaches toward Demon’s Souls, so close that they together almost constitute a shared world or set of parallel universes across which the soul of the franchise has been transmigrating.

Yet, the cunning struggle for survival of Werdna , King’s Field, or Demon’s Souls isn’t necessarily morally evil, although options abound to pursue that Faustian path of greedy destruction. Rather, the games thrive on players who face the grim darkness in which they are thrown and then thrive on it through caution and cunning. There is a place where difficult mechanics, diabolic puzzles, a gorgeously dark color palette, an infernally twisted storyline, neoclassical heavy metal, and an immersive first-person perspective all meet. That’s the place that I perpetually strive for as a player and a designer. It’s a place that subverts and transcends genre, turning RPG’s into adventure games, adventure games into survival horror, and survival horror back into into RPG’s. These games teach us that when we are are thrown into a grim and cruel world, our best response is to fall back on our wits, becoming cunning and methodical. The eponymous Dark Project of the first Thief is literally the Trickster’s attempt to give free rein over the world, but it is also the dark project in which Garrett and, by extension, the player engages in order to survive in this world of shadows and deception. If you can’t beat them, join them.

Nothing is true, everything is permitted.

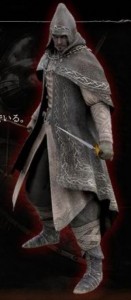

Stay tuned for Chaos magick, Hassan i Sabbah, William S. Burroughs, and Assassin’s Creed . . .