One of the reasons that I adore the Assassin’s Creed franchise comes from the paradox of the title’s creed, “Nothing is true, everything is permitted,” which is quoted several times in the games. A creed is defined as a profession of belief, but the assassin’s creed is a profession of belief in nothing except pure freedom. The games explore the paradox of an anti-creed in their mechanics and narrative design, which would deserve many pages to unfold analytically.

But what I’m especially interested in is a further wrinkle in the paradox: the mystical and magickal background of this statement as derived from its roots in history. The author of “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” was Hassan I Sabbah, an Islamic mystic belonging to the Ismaili sect. Ismaili mysticism is not the same as nihilism: rather, it entails (like many schools of mysticism) the idea that the visible, physical world is unreal in comparison to a higher, divine reality of ideas. Because the physical and social world is not true in comparison to the higher reality of Allah, an Ismaili initiate is freed from all laws. This notion of a liberating transcendent reality that renders null the laws of the world is an antinomian religious notion (from “anti” and “nomos,” against the law) contrary to the nihilism advocated by thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche, who saw in Hassan I Sabbah and the assassins a rejection of all transcendent values. Hakim Bey, a pseudonym of scholar and Sufi mystic Peter Lamborn Wilson, is responsible for analyzing and popularizing Hassan I Sabbah’s Islamic mysticism in the book Scandalous: Essays on Islamic Heresy, with the chapter on the assassins reproduced here.

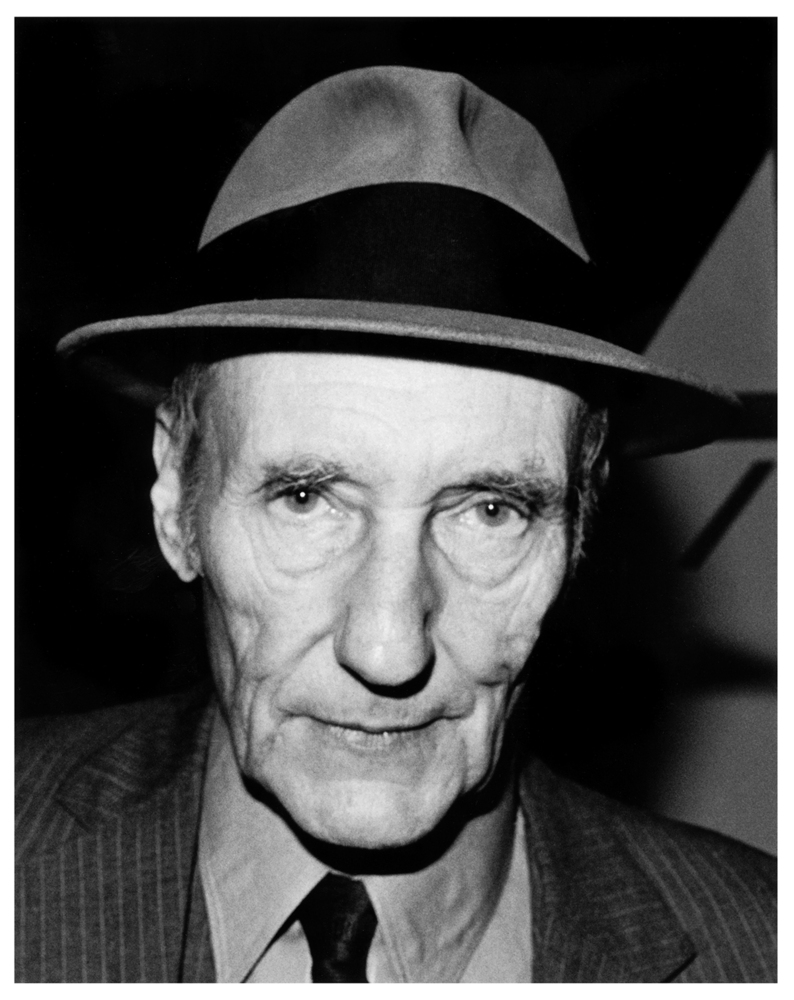

But the figure most responsible for promulgating the phrase “nothing is true, everything is permitted” is actually the beat writer William S. Burroughs, who acknowledges Hakim Bey as one of his primary sources. The novel Cities of the Red Night contains a large section that consists of permutations of the phrase, along with copious references to Hassan I Sabbah. Burroughs also quotes Hassan I Sabbah at the end of a long “invocation” before the novel: an invocation which is overtly magickal in the tradition of Western esotericism. After paying tribute to a pantheon of savagely violent and lascivious gods, goddesses, and demons, Burroughs wraps up with the following dedication and call to arms “to Hassan I sabbah, Master of the Assassins. To all the scribes and artists and practitioners of magic through whom these spirits have been manifested… NOTHING IS TRUE. EVERYTHING IS PERMITTED” (italics in original).

This use of a magical invocation is not merely formal. Burroughs was an initiate of the Illuminates of Thanateros (IOT), a group dedicated to “chaos magick,” a form of ceremonial magick developed by Peter Carroll and descended from figures like Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare. Burroughs’ former literary executor James Grauerholz states that Burroughs “was very serious about his studies in, and initiation into the I.O.T.”

Retired IOT official Douglas Grant elaborates:

“Through a mutual interest in Hassan Ibn Sabbah, contact was made with William S. Burroughs. William expressed interest in the IOT and was subsequently initiated into the IOT, by myself and another Frater and Soror. William did not receive a honorary degree, he was put through an evening of ritual, that included a Retro Spell Casting Rite, a Invocation of Chaos, a Santeria Rite as well as the Neophyte Ritual inducting William into the IOT as a full member. Though it is not included in the list of items buried with William… James Grauerholz assured me that William was buried with his IOT Initiate ring.”

All of this led up to Burroughs’ statement that “Magic is dangerous or it is nothing,” quoted in his introduction to Between Spaces: Selected Rituals and Essays from the Archives of Templum Nigri Solis.

This statement implies that magick is at its heart both counterfactual and countercultural: it resists the status quo, both metaphysically and culturally. And that’s why there’s more productive inspiration for magic in systems in occultists like Aleister Crowley than in any recent series of popular children’s books: in order to live up to its claim of metaphysical otherworldliness, magick ought to be subversive, out at the fringes of worldviews and consciousness. I’d like to see more of this sense of danger in magic systems within games, and that’s why I tend to be interested in the meeting of horror and magic in what I call the daimonic sublime. A previous post on Thief’s Garrett as magician suggests that magic can exist in game contexts other than RPG magic systems, and Altair’s social stealth is closely modeled after the Ismaili concept of “concealment” (hiding in plain sight by seeming to accept the norms of social behavior as a means of accomplishing one’s secondary agenda). The consequences of this mystical and historical background in how we play and read Assassin’s Creed, and how we design magic systems and stealth games, belongs in another post.

But first, the next post blog post will be about the King’s Field series, followed by Hungry Ghosts (which, two hours in, is clearly the best game I’ve played this summer).

We are interested of the picture of Burroughs on your Website. Can you help us? Thank you so much!

Best wishes,

Dorothee Binder

@Dorothee: Thanks for your interest. Alas, I found the image of William S. Burroughs via google image search and do not know its original source. A well-illustrated biography of Burroughs might help you track down the image.

Burroughs inspired Hakim Bey, not the other way around.

Nevertheless it’s a great, great article!!

Thank you, Brian, for both the correction and the feedback. Both are much appreciated.

Just wanted to say I’ve been back to this page three times in the past few months. Thank you for putting it out there. :3

Cool, Gira. Glad you’re enjoying the page.